By Steve Louis

You know the drill. A recession comes out of nowhere and in order to survive, businesses are forced to slash expenses, with layoffs being the first of many painful budget cuts.

Now all of a sudden the firm is understaffed which forces the remaining employees to perform dual roles, causing them to split their focus across multiple fast-paced, continually changing projects.

This multi-tasking inevitably leads to errors and omissions which result in additional costs that the project did not forecast. And without sufficient capital to cover the unexpected cost overruns, the company is again obliged to reduce costs.

And the downward spiral continues.

So how do we break the cycle? Or perhaps the first question should be, where do we break it?

Assuming that the organization is placing more and more responsibilities on the employees, the challenge is how to actually ‘do more with less’ while catching errors and recognizing changes before they adversely affect project performance.

These opportunities to break the cycle occur at the middle management level. Executives roll out their cost reduction strategy for mid-level managers to carry out, regardless of whether they even know how to do so. But there is one tool that is at every manager’s disposal, and that is:

Defining Objectives & Assumptions

Back in my managerial days, my department was challenged to deliver several complex subsea structures within a tight budget and timeframe. The real difficulty in achieving our goal was based on the fact that numerous key variables had yet to be provided by the client.

Historically. in our haste to get started (mainly due to the Project Manager’s need to recognize progress to trigger an invoice) we would prematurely kickoff the project and invariably redo engineering over and over again as the inputs were slowly received. Not only was this a frustrating waste of time, but it was extremely costly and would end up eating into our already slim margins.

The challenge is how to actually ‘do more with less’ while catching errors and poorly communicated changes before they adversely affect project performance.

So instead of jumping straight into the design phase, we developed a set of objectives that would set the tone for the entire project. This included physical parameters such as a maximum weight and overall dimensions but also ‘Business Critical Objectives’ – Zero (major) redesigns, Zero schedule delays, and Zero cost overruns.

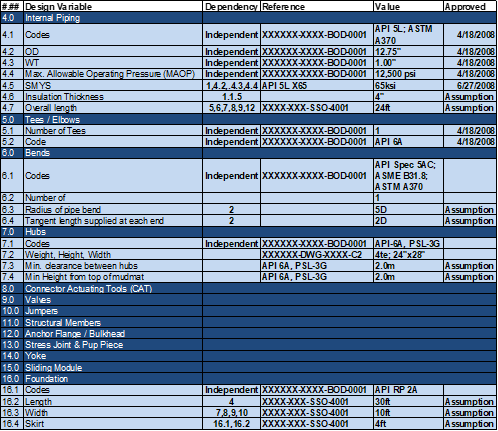

To offset the problem of dealing with so many unknowns, I created a Key Variable Matrix (KV Matrix), basically a menu of every component broken down into the relevant variables. Then I linked all the components together that were dependent upon each other. This allowed us to identify an acceptable range of assumptions that resulted in the fewest conflicts so that we could confidently start certain elements of the design.

A simplified example is shown below where the design of the piping is based on the hubs, tees, bends, and valve configuration, which ultimately controls the design of the mat foundation.

Simplified Example of a Key Variable Matrix (KVM) created by Steve Louis

Some engineers questioned why particular components were slightly oversized or overdesigned using my KV method. To that I referred back to our Business Critical Objectives (BCOs) which we defined at the start of the project – No redesigns, No delays, No cost overruns. The primary objective was not to have the lightest or smallest subsea structure, although those were secondary goals. The main objective was to deliver a reliable, functional product on time and at cost, therefore keeping my understaffed engineers focused and productive.

Integrated Quality Management System

The second tool that helped us achieve our BCOs and which can break the vicious cycle of doom is with an integrated Quality Management System (QMS). Many of us assume that a QMS is simply a collection of policies and procedures that is created early on in a company’s life, only to be referenced when an issue occurs.

Although this may be a reality for some companies, the successful ones utilize their QMS on a daily basis to reduce waste, improve processes, engage employees, prevent mistakes, lower costs and deliver consistent results.

The principles of Quality Management extend across the entire value chain

We employed quality management principles early and often, starting with the use of ‘lessons learned’. At the onset of each project, I would require our engineers to review our Lessons Learned database and present those relevant lessons for the new project. By having both a process AND a system that was easy to access and search we avoided thousands of hours of potentially repeatable mistakes. Our lessons were actually learned not just captured, or as the case with many companies, simply lost.

Now despite our best efforts, plans would change and we occasionally made mistakes. But the best way to manage those unanticipated events was through open channels of communication that alerted all relevant parties the instant it happened. This was made possible by the active presence of a Quality Manager who was integrated into the entire delivery process and accepted by the entire project team given the culture of collaboration and transparency that we all subscribed to.

We Want to Hear from You

What initiatives have you implemented in your organization that have helped break the dreaded Cycle of Doom which negatively impacts so many companies? Comment below or send a message to slouis@eternal-nrg.com.

About the Author

Steve Louis is a Managing Director at Eternal Energy LLC based in Houston Texas. Eternal Energy is a business advisory firm which has helped a number of clients at various stages of their growth including project management. He can be reached at slouis@eternal-nrg.com or by visiting www.eternal-nrg.com.

Enjoy what you read here? Looking to save time and energy for what matters most?

Texas Quality Assurance www.TexasQA.com

TQA Cloud QMS Software www.TQACloud.com

Email: info@texasqa.com | Tel: (512)548-9001

LinkedIn | Facebook | Instagram | Twitter(X) | YouTube

Quality Management Simplified

QMS Software | Consultation | FQM | Auditing

#QualityMatters podcast is streaming on

iTunes | Spotify | Audible | YouTube